Japan’s government in flux after election gives no party majority

TOKYO — The makeup of Japan’s future government was in flux on Monday after voters punished Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s scandal-tainted ruling coalition in a weekend election, leaving no party with a clear mandate to lead the world’s fourth-largest economy.

The uncertainty sent the yen currency to a three-month low as analysts prepared for days, or possibly weeks, of political wrangling to form a government and potentially a change of leader.

It comes as the country faces economic headwinds, a tense security situation fueled by an assertive China and nuclear-armed North Korea, and a week before U.S. voters head to the polls in another unpredictable election.

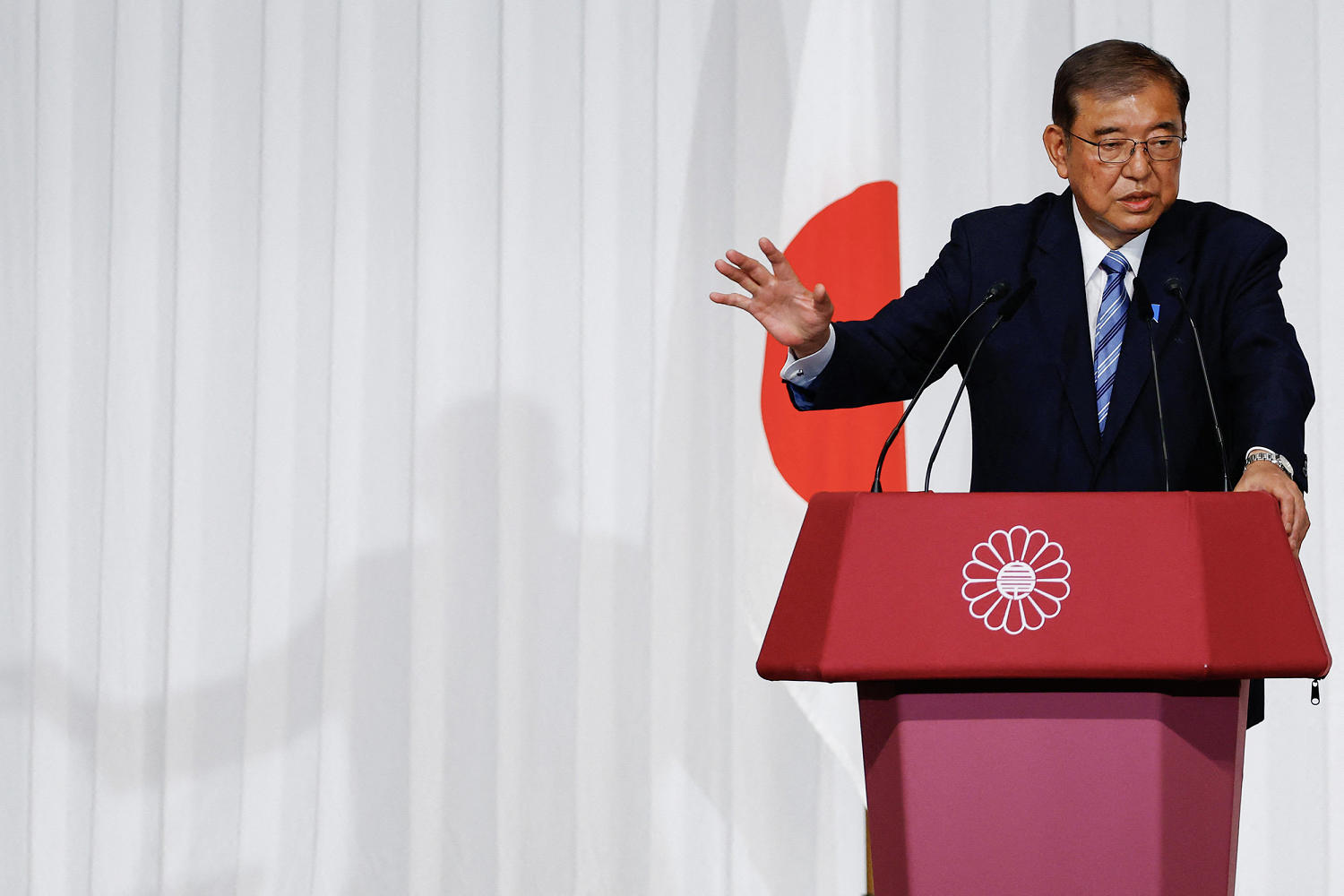

“We cannot allow not even a moment of stagnation as we face very difficult situations both in our security and economic environments,” a defiant Ishiba said at a news conference held Monday, pledging to continue as premier.

Ishiba’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its junior coalition partner Komeito took 215 seats in the lower house of parliament, down from 279 seats, as voters punished the incumbents over a funding scandal and a cost-of-living crunch. Two cabinet ministers and Komeito’s leader, Keiichi Ishii, lost their seats.

The biggest winner of the night, the main opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), had 148 seats, up from 98 previously, but also still well short of the 233 majority.

As mandated by the constitution, the parties now have 30 days to figure out a grouping that can govern, and there remains uncertainty over how long Ishiba — who became premier less than a month ago — can survive after the drubbing. Smaller parties also made gains and their role in negotiations could prove key.

“It seems unlikely that he (Ishiba) will survive to lead a new government as prime minister … though it is possible he could stay on as caretaker,” said Tobias Harris, founder of Japan Foresight, a political risk advisory firm.

CDPJ leader Yoshihiko Noda has said he will work with other parties to try and oust the incumbents, though analysts see this as a more remote possibility.

The LDP has ruled Japan for almost all of its post-war history and the result marked its worst election since it briefly lost power in 2009 to a precursor of the CDPJ.

Ishiba, picked in a close-fought race to lead the LDP late last month, called the snap poll a year before it was due in an effort to secure a public mandate.

His initial ratings suggested he might be able to capitalize on his personal popularity, but like his predecessor, Fumio Kishida, he was undone by resentment over his handling of a scandal involving unrecorded donations to LDP lawmakers.

Ishiba’s LDP declined to endorse several scandal-tainted candidates in the election. But days before the vote, a newspaper affiliated with the Japan Communist Party reported that the party had provided campaign funds to branches headed by non-endorsed candidates.

The story was picked up widely by Japanese media despite Ishiba saying the money could not be used by non-endorsed candidates. “LDP’s payments to branches show utter lack of care for public image,” ran an editorial in the influential Asahi newspaper two days before the election.

Support from smaller parties, such as the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) or the Japan Innovation Party (JIP), who won 28 and 38 seats, respectively, could now be key for the LDP.

DPP chief Yuichiro Tamaki and JIP leader Nobuyuki Baba have both said they would rule out joining the coalition but are open to ad hoc cooperation on certain issues.

Ishiba echoed that sentiment, saying “at this moment in time, we are not anticipating a coalition” with other opposition parties. The LDP will hold discussions with other parties and possibly take on some of their policy ideas, he added.

The DPP and JIP propose policies that could be challenging for the LDP and the Bank of Japan.

The DPP calls for halving Japan’s 10% sales tax until real wages rise, a policy not endorsed by the LDP, while both parties have criticized the BOJ’s efforts to raise interest rates and wean Japan off decades of monetary stimulus.

“It’s up to what can they give to these two parties to try and get them to just kind of join their side. The best scenario is getting them into the coalition government, but that’s a tall order,” said Rintaro Nishimura, an associate at consulting firm The Asia Group.

In a statement, the head of Japan’s most powerful business lobby Keidanren, Masakazu Tokura, said he hoped for a stable government centered on the LDP-Komeito coalition to steer an economy that faces urgent tasks such as improving energy security and maintaining the momentum for wage increases.

In one bright spot, a record 73 women were elected into Japan’s male-dominated parliament, surpassing 54 at the 2009 election.