Angela Merkel on Putin, Trump, and a post-Cold War world still divided

We met former German Chancellor Angela Merkel in a fitting place for her: the museum in Berlin dedicated to the Wall, that great symbol of the Cold War division between East and West. Parts of the wall have been preserved as a reminder of those hard times, especially for someone who lived through them.

She said images of the wall still conjure up highly emotional memories for her.

I asked, “When you look at the wall, what comes to mind to you immediately?”

“Between the ages of seven and 35, I had to live with this wall,” she replied. “I was, so to speak, behind the wall, and couldn’t come to this side. And of course, that’s still very moving.”

CBS News

Merkel’s new book, “Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021” (published by St. Martin’s Press), is filled with moving memories of what it was like growing up in the Communist-controlled police state that was East Germany. Her family had moved there when she was an infant because her father, a Protestant pastor, was assigned to a church there. But it was the fall of the wall that spurred her political awakening, and jump-started a career nobody would have bet on: A woman, from the East, who would not only become Chancellor of Germany, but who would hold the job for 16 years; who would be called the most powerful woman in the world, and who would deal with its most powerful men.

It turns out, life in the East actually had given her one advantage for dealing with all those men in dark suits: Those bright pant suits of hers weren’t an accident. “In my book I write that maybe my love for colorful clothes is due to the fact that in the East, everything was very gray,” she said.

Merkel’s uniform became part of her identity, and helped her break through the American pop-cultural barrier, on “Saturday Night Live,” the way few European leaders could.

Merkel left power three years ago this week, and has gone into a kind of self-imposed political radio silence since then, keeping her recollections and opinions to herself.

Not anymore.

Among the more awkward memories: that first shocking, even embarrassing, meeting with President Donald Trump in 2017.

I said, “I think it’s fair to say your most difficult relationship with an American president was with President Trump in his first term. You talk about your first encounter in the Oval Office where he refused to shake your hand, and you say that it occurred to you that he was fascinated with Putin and with politicians with authoritarian and dictatorial traits. Why did you say that?”

“Why he didn’t want to shake my hand, that, you’d have to ask him,” Merkel replied. “I think he often conveyed a message with a handshake. With some men he shook hands for a long time.”

“What were you thinking? Should I reach over? Will we shake hands? Won’t we shake hands? What’s he trying to do?“

“I describe it in my book because it was so interesting. I whispered to him, ‘I think they want us to shake hands.’ And at that moment when I said it, I noticed that he wanted to convey a message. And I was quite naïve, telling him that they want us to shake hands.”

“But did you get what he was trying to do?” I asked. “Did you think, Oh, he’s going to play it that way, that’s how we’re going to do it?“

“Yeah, that’s the way it was. I left being convinced that multilateral cooperation would be difficult with Donald Trump,” Merkel replied. “You can make deals with Donald Trump because he always thinks in terms of advantage and disadvantage. But in my experience, win-win situations are not only good for one side, but for both sides. That’s not really his way of thinking.”

CBS News

Merkel’s book, which is being released around the world, went to press before last month’s election. In it, she wrote that she wishes “with all my heart that Kamala Harris defeats her competitor and becomes president.”

Of the election results, she said, “I was sad. First of all, I wanted a woman to win. I was also in favor of Hillary Clinton. And secondly, I’m closer to Kamala Harris’ political conviction. But the American voters have decided, and it was a democratic election.”

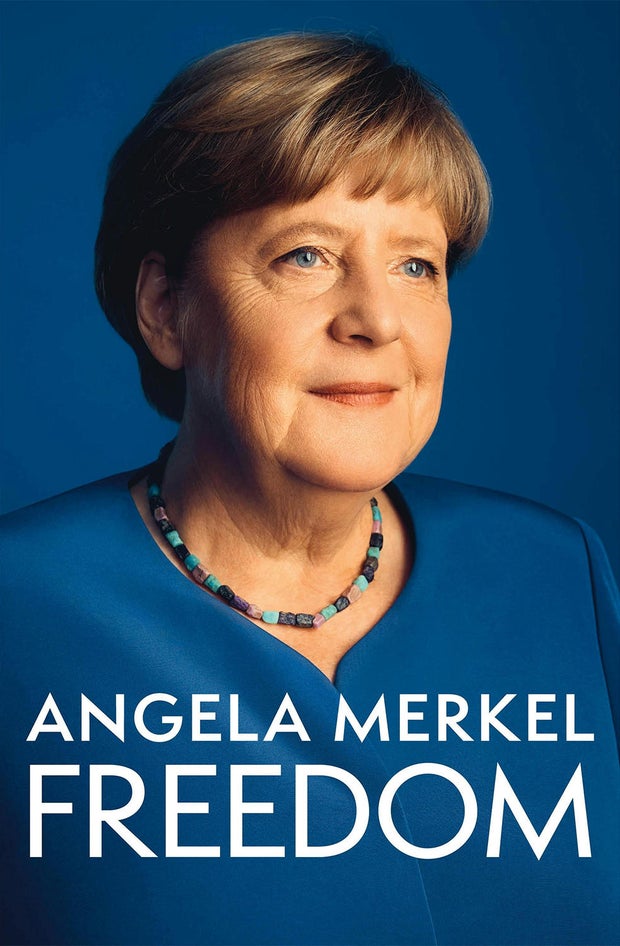

St. Martin’s Press

Merkel has come in for her own share of criticism since she left office. Her decision to allow more than a million refugees and migrants fleeing Syria into Germany is now often cited as a reason for the rise of anti-immigrant, right-wing political parties in Europe. She says those forces were on the rise anyway.

Her decision to allow the German economy to become too dependent on Russian natural gas is seen as another reason for Germany’s economic decline since the flow was stopped.

She says staying engaged with Vladimir Putin seemed like the right idea at the time, difficult though it was. And it didn’t stop him from invading Ukraine.

I asked, “You dealt a lot with Vladimir Putin. I take it, reading between the lines of your book, that you found him a very difficult and manipulative character as well, even an intimidating character at times. Famously, you don’t like dogs; he’d bring his dog to the meeting. Do you think he did that in an intimidating kind of way? And how would you suggest people deal with him, especially as things are heating up again?”

“Without fear,” she replied. “Of course, there are attempts to see how people react under a certain amount of pressure. And Putin can do that, too. And with the dog he expressed exactly that. But it all depends on how I manage the situation. I’m used to political pressure since childhood, so that did not shock me.”

Despite all her experience, Merkel says she now refrains from giving advice. But she does give hints. She says that, in general, she is worried about developments in the world: “I’ve always said that fear is not a good advisor. Times have become rougher. We are now sitting in a place where the world was divided in the Cold War, and then there was 1990. We had great hopes that things would become easier after the end of the Cold War. Things have not become easier.”

READ AN EXCERPT: “Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021” by Angela Merkel

Watch an extended interview with Angela Merkel about growing up in East Germany:

For more info:

Story produced by Erin Lyall and Anna Noryskiewicz. Editor: Jack Howell.