Husband of U.S. journalist detained in Russia: “I’m not going to give up”

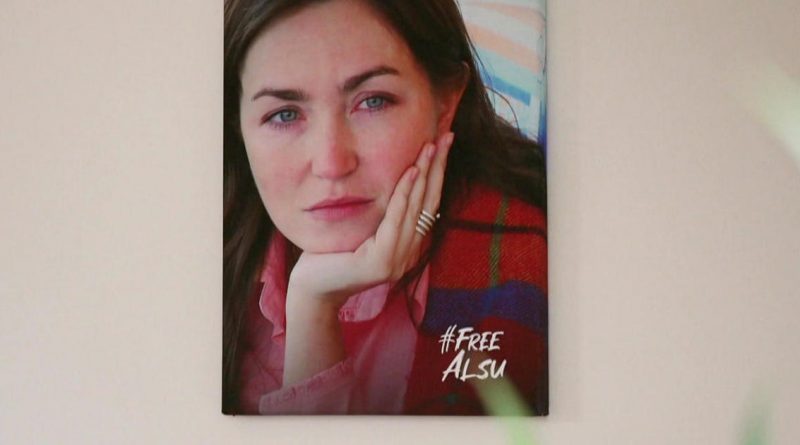

Fifteen-year-old Bibi Butorin has not been at home with her mom in Prague since last spring. Her mother, Alsu Kurmasheva, an American-Russian journalist, is now detained in Russia. “My mom is definitely my biggest inspiration,” Bibi said. “And I just miss her, like, more than I can possibly say. And I worry about her safety so much.”

She said her family understood that it was a risk for her mom to go to Russia: “But she was only going to go for two weeks, and it was for my sick grandmother.”

Kurmasheva was about to return in June from that personal visit to Kazan, when Russian authorities confiscated her passports. She’d not reported her U.S. citizenship. Kurmasheva was permitted to stay with her mom, until October. That was when masked police officers came knocking on her mother’s apartment door, and took Kurmasheva away.

CBS News

It’s turned Pavel Butorin into a single dad of sorts. Their girls both have U.S. citizenship like their mom. “She is in jail in Russia because she is an American citizen, and because she’s a journalist,” said Pavel. “And it seems like the Russian government is just building more cases against her.”

Kurmasheva’s pre-trial detention was extended until April 5. She’s facing charges of failure to self-register as a foreign agent, and disseminating false information about the Russian army, which could mean prison sentences of up to five and ten years, respectively.

Kurmasheva is listed as an editor on a book, “Saying No to War,” featuring stories of everyday people who oppose Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “I know that this book is a problem; it’s featured in her case file,” said Pavel. “There is nothing incendiary, nothing criminal about these stories. There’s no calls for violence in the book. It’s just opinions – not even Alsu’s opinions. But as a journalist, she certainly has the right to collect and publish any opinions.”

Butorin and Kurmasheva are both journalists with the Prague-based Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty (RFE/RL). It’s funded by U.S. taxpayers but is editorially independent, and reports news in 27 languages and 23 countries, including Iran and Afghanistan.

Steve Capus is RFE/RL’s president. “When freedom of expression is being shut down in one place after another after another, when the lights are turned out in one place, we turn them back on,” he said. “Our place is committed to the fundamental practice of accurate journalism where it might not otherwise be practiced these days.”

That puts his journalists at risk.

Capus, who’s worked at CBS and NBC, keeps photos of Kurmasheva and three other RFE/RL journalists who are currently detained (one in Russian-controlled Crimea, and two in Belarus) next to pictures of reporters who’d died while on duty.

“It has a way of kind of grabbing you and making you pay attention, and realize there’s an awful lot at stake here now – and never forget that they need to come home,” Capus said.

They’re in regular contact with the Wall Street Journal, whose reporter, 32-year-old American Evan Gershkovich, is also detained in Russia, arrested on espionage charges.

Doane asked, “Many Americans have not heard of Alsu. Why is Alsu’s name not as familiar to Americans?”

“It should be,” said Capus. “President Biden brought her up by name at the end of December. All of us are working our contacts to get as much attention for her case as we can.”

Jodie Ginsberg, who runs the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), in New York, calls Kurmasheva’s case “extremely worrying.”

She says that since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the detention of journalists has happened much more frequently. “New laws are brought in that make it extremely difficult to report on the war,” Ginsberg said. “Even calling it a war can bring you a jail sentence.”

Globally CPJ figures there are 320 journalists jailed for their work. Most are imprisoned for reporting in their own countries, with nearly half in just five nations (Russia, Iran, China, Myanmar and Belarus).

“That’s, I think, a reflection of the democratic decline we’ve seen over a number of years,” Ginsberg said.

CBS News

Of the 17 foreign journalists detained worldwide, 12 are jailed in Russia. Ginsberg calls it “state-sponsored hostage-taking.” She said, “There’s a two-fold effect when you arrest a journalist, particularly when you arrest a journalist with foreign citizenship, as we see in Alsu and Evan’s case: You have a political prisoner, so you have someone with which to negotiate with the U.S.; but this kind of action sends a powerful message to all journalists that they are not welcome.”

The U.S. classifies Gershkovich as “wrongfully detained,” but has not yet given that status to Kurmasheva. The State Department told “Sunday Morning” it’s “deeply concerned” about Kurmasheva’s detention, and continues to seek access to her, noting it “continuously reviews the circumstances surrounding the detentions of U.S. nationals overseas.”

Ginsberg said, “What happens when you designate an individual, a U.S. citizen, as ‘wrongfully detained’ is, you bring more resources from the government on their case. And now we really need to make her case as well-known as Evan’s. It’s really important that both of them, and all the journalists wrongfully detained, are freed.”

Efforts to raise Kurmasheva’s profile are underway, from a billboard in Times Square, to a group of friends gathering at a Prague restaurant.

Todd Benson, from Seattle, said Pavel Butorin and his girls are showing a great face since Alsu’s detention: “But I think, deep down, they’re hurting.”

And that hurt surfaced while Pavel was reading a note his wife sent from jail: “Celebrate freedom and love, Alsu.”

Declaring her “wrongfully detained” is up to the U.S. government. Ultimately, Alsu Kurmasheva’s fate is to be decided by the Russians. So, for now, Pavel tries to control what he can. “I need to keep it together,” he said. “I don’t want emotion to get involved.”

Doane said, “I think anyone would understand being emotional…”

“Maybe that’s what they want – maybe they want us to break down and surrender and give up,” said Pavel. “I’m not going to give up. We will not rest until we see Alsu here with her family at home.”

For more info:

Story produced by Julie Kracov and Duarte Dias. Editor: Carol Ross.

See also: